Sanitation

Safe sanitation is essential to reduce deaths from infectious disease, prevent malnutrition and provide dignity.

Having access to safe sanitation facilties is one of our most basic human needs.

But more than 40% of the world do not have access to safe sanitation. This is major health risk. Unsafe sanitation is responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths each year.

In this article we give an overview of global and national data on access to sanitation, and its impact on health outcomes.

Unsafe sanitation is a leading risk factor for death

Unsafe sanitation is responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths each year

Unsafe sanitation is one of the world's largest health and environmental problems – particularly for the poorest in the world.

The Global Burden of Disease is a major global study on the causes and risk factors for death and disease published in the medical journal The Lancet.

These estimates of the annual number of deaths attributed to a wide range of risk factors are shown here.

Lack of access to poor sanitation is a leading risk factor for infectious diseases, including cholera, diarrhoea, dysentery, hepatitis A, typhoid and polio.1 It also exacerbates malnutrition, and in particular, childhood stunting. In the chart we see that it ranks as a very important risk factor for death globally.

According to the Global Burden of Disease study more than 700,000 people died prematurely each year as a result of poor sanitation. To put this into context: this was almost double the number of homicides.

The global distribution of deaths from sanitation

In low-income countries poor sanitation accounts for a significant share of deaths

Poor sanitation contributes to more than 1% of deaths globally each year.

In low-income countries, it accounts for around 5% of deaths.

In the map here we see the share of annual deaths attributed to unsafe sanitation across the world.

When we compare the share of deaths attributed to unsafe sanitation either over time or between countries, we are not only comparing the extent of sanitation, but its severity in the context of other risk factors for death. Sanitation's share does not only depend on how many die prematurely from it, but what else people are dying from and how this is changing.

Death rates are much higher in low-income countries

Death rates from unsafe sanitation give us an accurate comparison of differences in its mortality impacts between countries and over time. In contrast to the share of deaths that we studied before, death rates are not influenced by how other causes or risk factors for death are changing.

In this map we see death rates from unsafe sanitation across the world. Death rates measure the number of deaths per 100,000 people in a given country or region.

What becomes clear is the large differences in death rates between countries: rates are high in lower-income countries, particularly across Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia.

Rates are more than 1000-times higher in many low-income countries than in rich countries.

We see this relationship clearly when we plot death rates versus income, as shown here. There is a strong negative relationship: death rates decline as countries get richer.

Access to safe sanitation

Nearly half of the world do not have access to safe sanitation

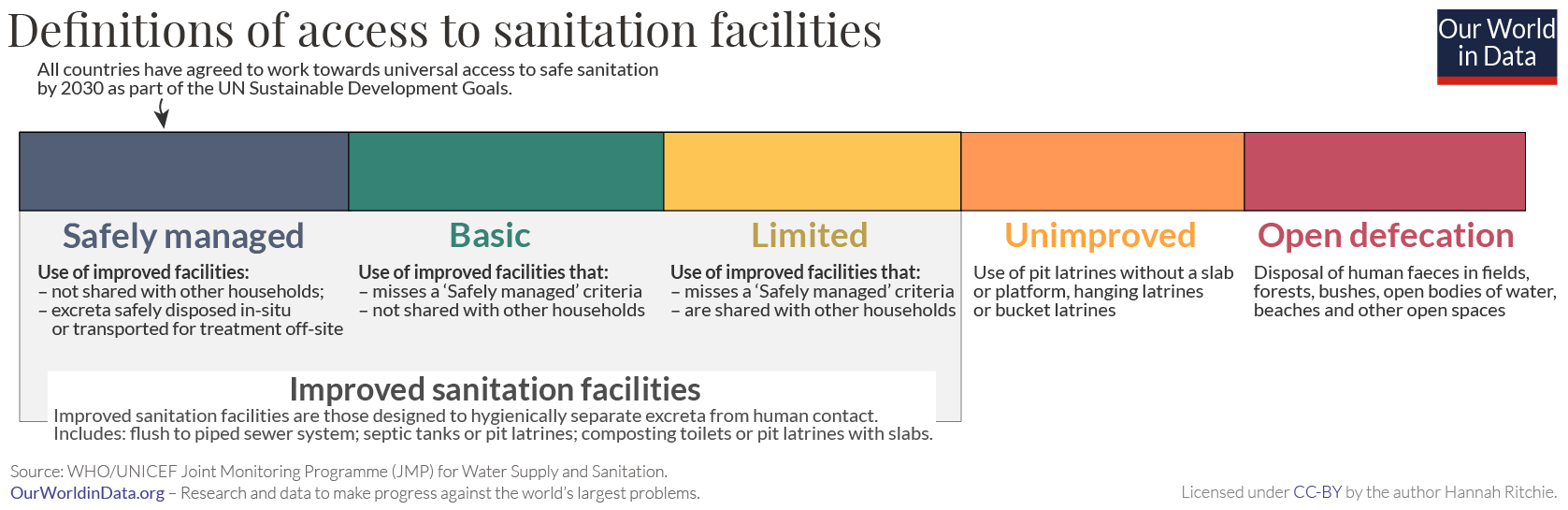

SDG Target 6.2 is to: “achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation” by 2030.

In 2020, just over half of the world population had access to safely managed sanitation. It is shocking that nearly one-in-two don’t. Many do not have any sanitation facilities at all, and instead have to practice open defecation.

In the chart we see the breakdown of sanitation access globally, and across regions and income groups. We see that in countries at the lowest incomes, less than one-fifth of the population have safe sanitation. Much like safe drinking water, most live in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The world has made progress in the last five years. But again, this has been far too slow albeit slightly faster than our progress on drinking water. In 2015 only 47% of the global population had safe sanitation. That means we’ve seen an increase of seven percentage points over five years.

In the map shown we see the share of people across the world that have access to safely managed sanitation.

How many people do not have access to safe sanitation?

In the map shown we see the number of people across the world that do not have access to safely managed sanitation.

Access to improved sanitation

What share of people do not have access to improved sanitation?

'Improved' sanitation is defined as facilities which ensure hygienic separation of human excreta from human contact. This includes facilities such as flush/pour flush (to piped sewer system, septic tank, pit latrine), ventilated improved pit (VIP) latrine, pit latrine with slab, and a composting toilet. Note that having access to improved sanitation facilities greatly increases the likelihood – but doesn't guarantee – that people use safe sanitation facilities. We look at coverage of safe sanitation here.

In 2020, almost one-third of people do not have access to improved sanitation.

In the map shown we see the share of people across the world that do not have access to improved sanitation.

How many people do not have access to improved sanitation?

In the map shown we see the number of people across the world that do not have access to improved sanitation.

Open defecation

What share of people practice open defecation?

Open defecation refers to the defecation in the open, such as in fields, forest, bushes, open bodies of water, on beaches, in other open spaces or disposed of with solid waste. Open defecation has a number of negative health and social impacts, including the spread of infectious diseases, diarrhoea (especially in children), adverse health outcomes in pregnancy, malnutrition, as well as increased vulnerability to violence — particularly for women and girls.2

The map shows the share of people practicing open defecation across the world.

What determines levels of sanitation access?

Access to sanitation facilities increases with income

The provision of sanitation facilities tends to increase with income. In the chart we see the share of the population with access to improved sanitation versus gross domestic product (GDP) per capita.

Overall, we see a strong relationship between the two: access to improved sanitation increases as countries get richer.

Open defecation is mainly a rural issue

As we see above, rural access to improved sanitation facilities typically lags behind urban areas for most countries. Although having access to improved sanitation facilities does not necessitate open defecation (some households can have very basic or shared sanitation facilities), we also see that open defecation is predominantly a rural issue for most countries.

In the chart we see the prevalence of open defecation in rural areas versus urban areas. For the majority of countries, open defecation in urban areas is typically below 20 percent of the population. For rural populations, however, the share of the population practicing open defecation can range from less than 20 percent to almost 90 percent. Although open defecation in urban areas is still a pressing in many countries, the problem much more strongly concentrated in rural areas.

Other health impacts of poor sanitation

Stunting is higher where access to improved sanitation is low

Stunting — determined as having a height which falls below the median height-for-age WHO Child Growth Standards — is a sign of chronic malnutrition.3

Although, linked to poor nutritional intake (which we cover in our entry on Hunger and Undernourishment), it is linked to a range of compounding factors, including the recurrence of infectious diseases, childhood diarrhea, and poor sanitation & hygeine.

In the chart we see the prevalence of stunting (measured as the share of children under 5-years-old defined as being more than two standard deviations below the median international height) versus the share of the population with improved sanitation facilities. Overall we see a negative correlation: rates of childhood stunting are typically higher in countries with lower access to improved sanitation facilities.

Definitions

Improved sanitation facilities: "An improved sanitation facility is defined as one that hygienically separates human excreta from human contact. They include flush/pour flush (to piped sewer system, septic tank, pit latrine), ventilated improved pit (VIP) latrine, pit latrine with slab, and composting toilet.

Improved sanitation facilities range from simple but protected pit latrines to flush toilets with a sewerage connection. To be effective, facilities must be correctly constructed and properly maintained." 4

Safely managed sanitation facilities: “Safely managed sanitation” is defined as the use of an improved sanitation facility which is not shared with other households and where:

- excreta is safely disposed in situ or

- excreta is transported and treated off-site.

The definitions of categories of sanitation facilities coverage include:

- 'Basic service': Private improved facility which separates excreta from human contact;

- 'Limited service': Improved facility shared with other households;

- 'Unimproved service': Unimproved facility which does not separate excreta from human contact;

- 'No service': open defecation.

Open defecation: "People practicing open defecation refers to the percentage of the population defecating in the open, such as in fields, forest, bushes, open bodies of water, on beaches, in other open spaces or disposed of with solid waste."

Endnotes

WHO (2019) – Fact sheet – Drinking water. Updated June 2019. Online here.

Mara, D. (2017). The elimination of open defecation and its adverse health effects: a moral imperative for governments and development professionals. Journal of Water Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 7(1), 1-12. Available online.

World Health Organization (2014). WHA Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Stunting Policy Brief. Available online.

World Bank & WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme ( JMP ) for Water Supply and Sanitation. World Development Indicators Metadata. Available online.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Hannah Ritchie, Fiona Spooner and Max Roser (2019) - "Sanitation". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/sanitation' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-sanitation,

author = {Hannah Ritchie and Fiona Spooner and Max Roser},

title = {Sanitation},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2019},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/sanitation}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.